Untangling Europe's digital rights

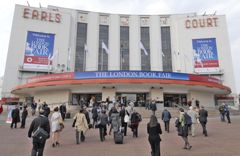

Tom Wilkie reports back from the London Book Fair, where rights management was a hot topic for discussion

The cloud of ash from Iceland’s volcanic eruption left its mark at this year’s London Book Fair from 19 to 21 April. Several large and imposing stands in the exhibition hall stood empty, due to the travel disruption, while seminars and speeches at the conference sessions had to be hurriedly cancelled or curtailed.

The cloud might almost serve as a metaphor for the difficulties disrupting digital access to books and other publications. But in the case of digitised works, it is a cloud of uncertainty over the law and politics of digital rights management.

The issue of digital rights management is centre stage in the ambitious projects to enable anyone, anywhere in the world, to access European literature and culture digitally.

One major digitisation project is The European Library, a network organisation headquartered at the National Library of The Netherlands. It was set up to ensure ‘equal access and to promote worldwide understanding of the richness and diversity of European culture and learning’, according to Sally Chambers, collections manager for The European Library.

This project brings together the national libraries of 48 European countries in 35 languages. It acts as a portal, with a user interface in all 35 languages – although multilingual searching is still a problem, Chambers said. In addition, some libraries have provided catalogues from their countries’ research libraries as well as the national library and 14 national libraries have digitised text from their collections and provided full text content to the European Library.

The project has developed over more than a decade, from the earliest attempts in the Gabriel (GAteway and BRIdge to Europe’s National Libraries) project to bring all national library catalogues into one central index using an Open Access initiative (OAI) metadata harvesting protocol. The library is now embarking on work to transcend national boundaries and create language-specific catalogues so that, for example, readers can search all books in German, even if they had been published in France or Bulgaria.

The European Library also acts as the library-driven aggregator for Europeana, a single multilingual access point for digital access to European cultural heritage. The ambit of Europeana is much wider than the European Library and includes museum objects such as paintings, sculpture and specimens; it also involves archives of Government papers, court records, census data, diaries and letters; as well as audiovisual materials. The European Library is just one of many content (or at least, catalogue) providers to Europeana.

Currently the collection contains items from every EU country, amounting to more than 7.5 million items, with some 4.3 million images (pictures, postcards, posters) and 2.5 million texts.

However, the geographical spread of contributions from EU countries is very unequal. As Viviane Reding, the EU Commission for the Information Society and Media, noted in August 2009, only five per cent of all the digitised books in Europe are currently in Europeana and more than half of Europe’s digitised works come from one country alone – France.

These ambitious European projects face difficult technical problems, not least in dealing with Europe’s polyglot languages. Other issues include the perennial question as to whether the MARC standard – MAchine Readable Cataloguing – is sufficiently robust and flexible to solve today’s problems of digitising libraries. This was discussed in questions at the conference with the slightly grudging conclusion that we are currently stuck with MARC.

But, as Graham Taylor, director of educational, academic, and professional publishing at the UK’s Publishers Association, identified at the book fair, one of the biggest issues underpinning such developments is that of rights management. Projects like The European Library represent ‘a case study in the management of intellectual property and copyright in the digital age’ that meet not only the social need for access to these works but also authors’ needs to earn ‘a dignified living’, he said.

The big challenge for such digitising projects, Taylor noted, is facilitating the search for rights information and asking rights holders for permission to digitise their work. In the USA this is going down the legal route, where a Class Action Suit concerning Google’s book digitisation project is currently working its way through the courts. ‘In Europe, it’s healthier’, he said, as ‘we are going down the legislative route.’

And another European project hopes to offer a solution too. Arrow – Accessible Registries of Rights Information and Orphan Works towards Europeana – is a single framework designed to manage rights information supporting the development of digital libraries in Europe. It will identify rights-holders and clarify the status of works as to whether they are out of print or orphan works – in copyright but with no information as to who the rights-holder is.

Speaking on behalf of Paola Mazzuchi, from the Italian Publishers’ Association, who is managing the Arrow project, Sally Chambers called this issue ‘the 20th century’s black hole in the digitising of libraries’. Most of the books that have been digitised so far are either antique – 19th century or earlier and so out of copyright – or are already in the public domain without copyright restrictions.

The search for rights-clearance is time- and resource-intensive and, if the owners cannot be traced, then the book has to be placed in the orphan category and cannot be digitised. This is holding up the digitisation of many 20th century works. According to one British Library estimate, as many as 40 per cent of 20th century books could fall into the orphan category. However, this figure was regarded as a gross overestimate by some at the meeting.

Arrow is a technical system offering a distributed rights information infrastructure, and a registry of orphan works. By the summer of this year, the alpha release will be running in Germany, the UK, Spain and France, with a further seven countries joining by February 2011.

There is, Chambers said, no formal link between the Arrow project and the Google Books Rights Registry, but as the technical aspects were very similar, staff from the two projects did meet and know each other. However, progress would depend on political and legal developments on each side of the Atlantic.