Scholarly publishing and the gender pay gap

It probably won’t come as news that there is a gender pay gap in scholarly publishing, say Alice Meadows and Lauren Kane

It probably won’t come as news that there is a gender pay gap in scholarly publishing. Even before the UK government’s decision to require organisations with more than 250 employees to report on their gender pay gap, US non-profit form 990s and other publicly available salary data revealed that a gap existed. Despite their industry majority, there is an under-representation of women in the industry’s most senior (and thus highest-paid) positions, contributing to this imbalance.

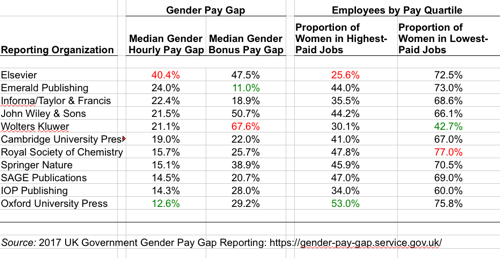

Newly released data for UK-based corporations corroborates this concern. Cambridge University Press (CUP), Elsevier, Emerald Publishing, Informa/Taylor & Francis, IOP Publishing, Oxford University Press (OUP), Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), SAGE, Springer Nature, Wiley, and Wolters Kluwer are among the over 10,000 organisations (commercial, governmental, and not-for-profit) that reported on their gender pay gap ahead of the recent deadline. Organisations with more than 250 UK-based employees were required to report on the proportion of men and women in each pay quartile, as well as on the mean and median pay and bonus pay for men and women.

As illustrated in the accompanying chart, with the exception of Wolters Kluwer there are far more women than men in the bottom pay quartile. Moreover, with the exception of OUP there are more men than women in the top quartile. Wolters Kluwer is unique in this group in that men in the company outnumber women overall. Most organisations report a gender split of around 55-65% women to men, in line with estimates of scholarly publishing overall. Yet in all organizations but OUP, less than half of the top pay quartile are women. And at Elsevier, with the lowest proportion of the group, women make up just a quarter (25.6%) of the top pay quartile.

One would hope and expect that the proportion of women to men would be roughly the same at every level of an organization. If it’s not, then presumably either the organisation is doing a poor job of recruitment –with many women at entry level, but few talented enough to be promoted to senior positions – or else the organisation is consciously or unconsciously favoring and promoting men over women.

As in every sector, some companies performed better than others, and the most equitable of those analysed have a median pay gap of less than the national average of 18.4%. However, even the best of the group, Oxford University Press, shows a gender pay gap of 12.6%, while Elsevier reported a whopping 40.4% gap. When it comes to bonuses, the differences are even starker, from an 11% gender bonus gap at Emerald Publishing to 67.6% at Wolters Kluwer.

Unsurprisingly, as in other sectors, most organisations that we analysed have put a somewhat positive spin on their respective situations. In a word, they are 'confident' that men and women are paid equally for doing the same jobs (obviously - because otherwise they’d be in breach of equal pay legislation). It’s just that, to quote the RSC: 'Women are overrepresented in the lower quartiles of pay. This is mainly due to women filling a higher proportion of our administrative and early career publishing roles.' Or this, from Wiley: 'Our mean and median bonus gaps are driven by our highest earners, who are predominantly male.' And, from Elsevier: 'The bonus pay gap statistics reflect the fact that opportunities to receive performance-related pay ... increase with seniority and the more senior the population, the higher the proportion of men to women.'

While these justifications provide little consolation, many of the organisations also included plans of action to address their gender pay gap. Examples include:

-

Signing up for initiatives like the Publishers Association 10-Point Inclusivity Action Plan (CUP, SAGE, Springer Nature)

-

Working toward EDGE accreditation (Elsevier, SAGE)

-

Changes to recruitment strategy (CUP, Informa/Taylor & Francis, OUP, SAGE

-

Flexible working practices (CUP, OUP, RSC, Springer Nature)

-

Unconscious bias training (CUP, RSC, SAGE)

The fact that these organisations must submit annually and make this data publicly available gives us hope for progress. And more data is being collected beyond this UK sample, through the Workplace Equity Project survey, the PA’s annual survey as part of their 10-point action plan, and the cross-industry proposal for examining diversity and inclusion. But we, as an industry, don’t have to wait for more data before making changes. We challenge all organisations in the scholarly publishing industry, whether or not legally required to do so, to proactively examine their salary data and take steps to address inequities based on gender, race, or other forms of discrimination.

Alice Meadows is director of community engagement and support for ORCID; Lauren Kane is chief strategy and operating officer at BioOne.

This is an abridged and modified version of an article that first appeared on The Scholarly Kitchen.