Catalyst for change: virus could impact on research

Research has long been a vital part of how we advance human knowledge to better understand our world and improve lives, writes Andrew Plume

In 2020 we have seen public recognition of the social function of science grow significantly. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the idea of ‘listening to the science’ has become a common refrain among those with the heavy burden of leading humanity out of crisis. Scrutiny of research and its practices is growing – whether it’s the conduct of vaccine clinical trials, or the evidence basis for government policies on wearing face masks or opening schools. To properly assess the impact of research (even in ‘normal’ times), we must apply the same high standards of evidence to the conduct and evaluation of research, as researchers apply in their own specialised fields.

A push to more responsible evaluation

The evaluation of research is constant and is inseparable from the research enterprise. From researchers evaluating one another for the purposes of career progression, expert review of manuscripts for publication in scholarly journals or grant applications for project funding, evaluation is baked in. Even the recognition of previous work through citation is a form of evaluation, with each citation acting as a link in the chain of the developing knowledge in a given field of investigation, contributing to the famously ‘self-correcting’ nature of science.

In the last decade, attention has become increasingly focussed on how evaluation processes can be made more fit for purpose and fair. Since 2013, the Declaration on Research Assessment has become a rallying point for many who wish for an end to the use of a small number of simplistic metrics, and instead seek a plurality of indictors of research achievement that goes far beyond direct influence on other researchers and into real-world impacts. In 2015, experts in research evaluation built further on this idea and published the Leiden Manifesto, a set of 10 principles for more responsible research evaluation; Elsevier recently endorsed these principles as part of its journey towards playing its part in making evaluation better by making it more evidence-based. Elsevier’s International Center for the Study of Research has been established to work in partnership with the research community to develop evaluative approaches aligned with the Leiden Manifesto principles.

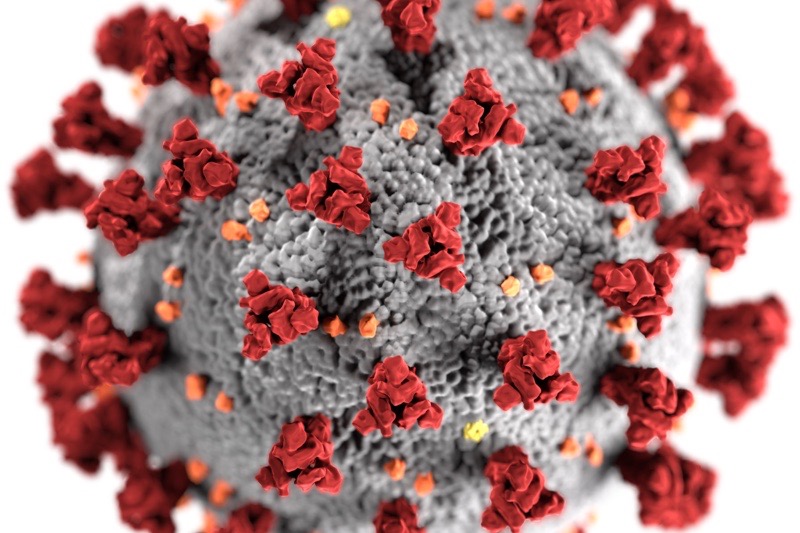

The impact of Covid-19

This year Covid-19 has completely shifted the way research can operate, with seismic change happening almost overnight. In many parts of the world research facilities have been forced to close at least temporarily or to divert their focus to Covid-19 work, hampering progress for researchers typically based in labs, libraries or large research faculties, such as telescopes or particle accelerators.

For field-based researchers, lockdowns have restricted free movement to research sites, which are their natural laboratories, limiting the potential for discoveries spanning archaeology to oceanography.

With the possibility of conducting new research temporarily restricted, many researchers have used the opportunity to write up completed work for publication in peer-reviewed journals. However, various analyses suggest that journal manuscript submissions and preprint postings from women researchers have fallen behind those from men, with one of the reasons suggested that women have disproportionately assumed other duties (such as home-schooling children and more) during the crisis. Taken together, it’s clear that not only may there be a short-term dip in the total production of new knowledge, but it will affect women more profoundly than men. Not only will their traditional indicators of productivity and impact (such as research publications and citations) be reduced, there is likely to be less diverse points of view in many fields.

Restrictions on travel and meetings of large groups of people have also had consequences for conferences, workshops and symposia which are the lifeblood of research. Serving partly as evaluative exercises in themselves (at which researchers can get expert feedback) and partly as networking and job fairs, they also permit a high degree of serendipitous discovery and connection. As conferences have been cancelled or moved to a more linear, stilted online format, so have chance meetings in the line for coffee that might lead to a new collaboration become far less likely.

Even in the relatively narrow fields of research most relevant to understanding the coronavirus at the heart of the current pandemic, we may observe changes in the way research is done in a crisis. A recent analysis of coronavirus research publications shows that in the initial months of the pandemic, research teams had fewer members from fewer different nations than before the emergence of Covid-19, but that certain international collaborations (notably between the US and China) thrived under the pandemic. This apparent tendency to retrench to established partnerships may prove to be a limited response to working to a critical short-term goal, but should give pause to those who might believe the rise of open and international collaboration is as inexorable as trends have suggested.

Reducing the impact

Covid-19 is clearly having a disruptive impact on how research is conducted, communicated, funded and evaluated. The likelihood is this disruption will continue for some time, while consequences for research discoveries and research careers are accumulated.

Close monitoring of the impact of the pandemic on research, turning the highest levels of research evidence-gathering back to the research enterprise itself, will arm us with the knowledge to reduce its negative impacts and discover the positives: changes the virus has catalysed that may be a force for good in research.

- Andrew Plume is president of the International Center for the Study of Research and senior director for research evaluation at Elsevier